- Contact us on - Contactez-nous sur - Contacte-nos em

- +233-30-277-8867/8

- +233-30-277-2548

- secam@secam.org

In Kenya’s Lodwar Diocese, “last stop before Hell,” Matthew 25 is a Mission Statement

In Kenya’s Lodwar Diocese, “last stop before Hell,” Matthew 25 is a Mission Statement

Crux || By Ines San Martin || 12 December 2017

In the northern Kenyan region bordering South Sudan, Uganda and Ethiopia, there’s a 30,000 square mile Catholic diocese once defined by a British travel writer as the “last stop before Hell.” A desert region, it’s plagued by drought, extreme heat, ethnic fighting, chronic poverty and hunger, and so isolated that political prisoners in the British colonial era were sent there to be forgotten.

In the northern Kenyan region bordering South Sudan, Uganda and Ethiopia, there’s a 30,000 square mile Catholic diocese once defined by a British travel writer as the “last stop before Hell.” A desert region, it’s plagued by drought, extreme heat, ethnic fighting, chronic poverty and hunger, and so isolated that political prisoners in the British colonial era were sent there to be forgotten.

The Diocese of Lodwar includes both the indigenous Turkana people and the Daassanach, an ethnic group originally from Ethiopia. Both practice a traditional pastoralist lifestyle of herding cattle, sheep and goats, so they have to move around over vast areas in search of grazing land. They’ve been stealing each other’s food for years, and the presence of guns in the area has turned their rivalry deadly.

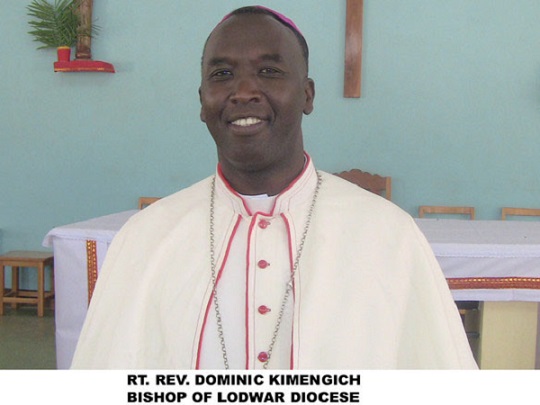

Leading the church in this periphery, among the world’s most poignant peripheries, is Bishop Dominic Kimengich, originally from Nakuru, some 75 miles northwest of Kenya’s capital city Nairobi. When he was appointed auxiliary bishop here in 2010, the archbishop who once ordained him a priest jokingly asked, “What did you do [wrong] to get sent there?”

Yet this Opus Dei prelate, who spent four years in Rome during his priestly formation, didn’t question the appointment. Nor did he hesitate when his predecessor’s retirement was accepted nine months later, and he was appointed the new bishop.

“I had no illusions, I knew it was going to be tough,” he told Crux on a blazing hot Friday morning in early December. “But the pope, the Church, asked me to come here, so I accepted the challenge.”

“You can’t last here if you’re not willing to sacrifice,” Kimerngich said about what ministry is like in such an environment. “When we have a new deacon, we’re very up front about it, making it very clear there are no resources whatsoever.”

Priests working in Lodwar receive no salaries. All they get is a monthly Mass stipend that works out to $1,200 a year, much of which they invest in gas for their vehicles to reach remote outstations, food for their residences, and helping the many people who look to them for help to purchase meager supplies of food, medicine, clothing, and other basic needs.

It’s been over six years since Kimengich came to Lodwar, and every day he said he could wake up overwhelmed by the weight that lies on his shoulders. Yet, he said, he’s found a way of handling the pressure.

“I know it’s not my work, I’m only a tool. I’ll do my best and He [pointing up] will do the rest,” he said.

This trust in God, he said, has been with him since the beginning of his priestly ministry, and he says he was never overcome by the feeling that he couldn’t move forward, or that whatever problem he was facing that day, he’d have to deal with it alone.

Problems, however, abound, and they’re straight out of the Gospel: Feeding the hungry, welcoming the stranger, visiting the imprisoned.

For instance, last year Kimengich was saying Mass to celebrate the 10th anniversary of a boarding school run by the diocese near the border with Ethiopia. Students from both the Turkana and Dassanach tribes attend the school and their parents attended the liturgy, under the assumption that guns were not allowed.

However, members of the Turkana, “probably after colluding with the doorman” who was also of their tribe, managed to bring guns into the church and opened fire, killing one of the Ethiopians.

“We failed as a Church,” Kimengich said. “They came thinking they were safe, but they ended up being scared, crying in one of the classrooms.”

The perpetrators managed to run away, “by the grace of God,” the bishop said — not because the killers escape justice, but because their absence prevented a further bloodbath. The man who pulled the trigger, Kimengich said, was trying to avenge 40 Kenyans who’d been killed by the Ethiopians in 2012.

The bishop then took the body of the victim back to the Dassanch tribe, while the rest of the Ethiopians remained under police protection on the other side of the border. Had the police not intervened, he said, “we would not have come out alive.”

During the funeral of the man, one of his daughters told the others not to cry, because sooner or later they would have their revenge.

The Catholic Church arrived in Lodwar, today a city of roughly 50,000 people, in 1961. Moved by a humanitarian crisis caused by a serious drought and resulting famine, two Irish missionary priests from the St. Patrick Society relocated to the area.

“The priests came to help organize the aid, and since then the people of Lodwar have associated the Church with assistance,” he said. With temperatures that can easily reach 130 degrees, he said “people were basically naked” when the missionaries arrived.

The most urgent needs back then were water and education, and they largely remain so today. After the original missionaries helped improve the water supply, the diocese’s first bishop focused much of his attention on schools, seeing it as the best investment.

Kimengich and his priests are once again tending to much of the people’s basic needs, doing what’s known as “primary evangelization,” meaning carrying the Gospel to people who’ve never heard it before.

Kimengich knows full well that some Turkana are drawn to the church not for its spiritual message, but its capacity to deliver concrete aid in times of need. Still, he’s sanguine about the situation.

“Many come to Mass for food, but when there’s nothing, they still come,” the bishop said. “If they come to Mass and there’s nothing, they’re going to die. We always have it clear that we are about more than food. Jesus fed the crowd, but he also challenged them.”

Among many projects the prelate has in mind is to build a Catholic hospital on land they’ve already acquired. The facility will be capable of providing treatment that the one local medical center cannot treat, including diseases such as cancer.

Though the existing institution has an X-Ray machine, if a patient needs a CT scan, the closest hospital with the equipment is in Nairobi. In addition, the situation is so dire that most of the patients going to the current hospital can’t afford an X-Ray, which costs about $3.

Another key concern is the massive Kakuma refugee camp, currently hosting some 200,000 refugees and located within the diocese. It was opened by the United Nations in 1992, with the arrival of the “Lost Boys of Sudan.” Today, it also hosts refugees from Somalia, South Sudan, Burundi, Uganda and Ethiopia.

Many of those people have fled violence, while others are what the bishop described as “education refugees,” meaning people who settle in the camps because they have better access to schools, lodging and even health care.

The diocese has a parish in Kakuma, and the bishop visits it several times a year to celebrate confirmations, on International Refugee Day, and for the graduation day of a virtual education program run by the Jesuit Refugee Service.

Visiting the camp, Kimengich said, “touches you in a very deep way, seeing how grateful they are to what they receive from the Church, helps you realize how fortunate you are to be able to help those suffering.”

Therefore, in the “last stop before Hell,” the Catholic Church strives quite literally to answer Christ’s famous appeal: “Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” Feeding the hungry, giving water to the thirsty, clothing the naked, looking after the sick, and welcoming the foreigner, are akin to a mission statement.

Living in Lodwar, Kimengich said, “is living the Gospel.”

“Matthew 25 is not theoretical here …. this is putting the faith into practice.”

Source: Crux…