- Contact us on - Contactez-nous sur - Contacte-nos em

- +233-30-277-8867/8

- +233-30-277-2548

- secam@secam.org

Black Spiritual Traditions have Long History in Catholic Church

Black Spiritual Traditions have Long History in Catholic Church

Global Sisters Reporter (GSR) || By Dawn Araujo-Hawkins || 19 March 2018

I got a crown up in-a that kingdom,

I got a crown up in-a that kingdom,

Ain’t-a that good news!

I got a crown up in-a that kingdom,

Ain’t-a that good news!

I’mma gonna lay down this world,

Gonna to shoulder up-a my cross,

Gonna to take it home-a to my Jesus,

Ain’t-a that good news!

— “Ain’t That Good News,” a Negro spiritual

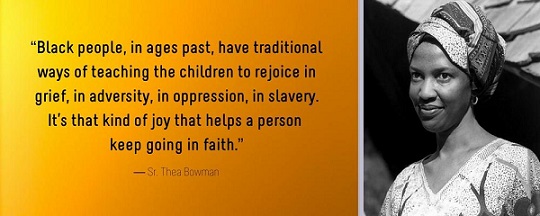

It’s been nearly 30 years since Sr. Thea Bowman famously declared to a gathering of the U.S. Catholic bishops that her “black self,” with all the black songs, dances and traditions she’d imbibed while growing up in Canton, Mississippi, was a gift to the church.

“That doesn’t frighten you, does it?” she asked them, her eyebrows raised.

By the time Bowman, a Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration, took the stage in front of the bishops, she was already something of a celebrity. The dashiki-wearing, gospel-singing black nun had been preaching the legitimacy of black religious expression in the Catholic church since the early 1960s. For that work, she’d been featured on “60 Minutes” and “The 700 Club” and invited all over the country to speak. Bowman was black and proud. And authentically Catholic.

The idea that black religious expression isn’t truly Catholic was and is pervasive, said C. Vanessa White, an assistant professor at Catholic Theological Union who teaches black spirituality, including a course on Bowman’s writings. Some white Catholics are quick to dismiss as non-Catholic anything — like Bowman’s gospel songs and Negro spirituals — that seem too black.

“People say, ‘Oh, you’re being Baptist; this is not Catholic,’ ” White said.

But what those people fail to understand, and what Bowman sought to explain, White continued, is that spirituality — the ways believers exist and act — is inherently cultural.

“If the leaders are all white, then that spirituality is going to be shaped by that cultural group,” she said.

European expressions of Catholicism aren’t dominant in the United States today because they’re the neutral standard; rather, they’re dominant because for centuries, only men of European descent were allowed to lead parishes.

Meanwhile, enslaved Africans and their descendants weren’t waiting for white churches to accept them as fully functioning members of the body of Christ. Confronted with the truth of the cross, they instead developed their own ways of thinking about and worshipping the God of deliverance.

“I got a Savior in-a that kingdom. Ain’t-a that good news!”

Black people, of course, are not a monolith. However, the shared experience of enduring the United States’ systematic brutality against them has left a real and observable mark on how black communities across denominations experience God.

“African American spirituality is the result of the encounter of a particular people with their God,” writes Catholic womanist theologian Diana Hayes in Forged in the Fiery Furnace: African American Spirituality. “The spirituality of African Americans expresses a hands-on, down-to-earth belief that God saw them as human beings created in God’s own image and likeness and intended them to be a free people.”

The so-called slave religion that developed in the United States syncretized the belief in a liberating Jehovah Jireh with the rituals and cosmologies carried over from the motherlands in West and Central Africa. However, because enslaved blacks were barred from institutional churches, this distinctly black expression of Christianity was cultivated in secret worship spaces known as hush harbors.

The hush harbors are where we find the foundations of more contemporary articulations of black spirituality. It’s where we find the roots of black gospel music, the black shouting tradition and black Christians’ proclivity to “catch the Holy Ghost.” In the hush harbors are the genesis of the black emphasis on communal worship and ministry, and — as Bowman explained in a 1984 interview with St. Anthony Messenger — the spirituality nurtured in the hush harbors laid the foundation for the eternal optimism of black eschatology and liberation theology.

“Black people, in ages past, have traditional ways of teaching the children to rejoice in grief, in adversity, in oppression, in slavery,” Bowman told the reporter at the time. “It’s that kind of joy that helps a person keep going in faith.”

Some Africans were already Catholic when they were trafficked to the United States between 1619 and 1860. Others were outfitted with Catholicism when they became the property of Catholic slaveholders in Maryland and Louisiana. But the majority of black Catholic families in the United States became Catholic after the Great Migration that began in 1915.

Forsaking the South, black people began moving en masse into the urban centers of the North, filling the vacancies in formerly white Catholic schools and churches created by white flight into the suburbs. And, as Hayes told Global Sisters Report, this period marked a change in black religious expression.

Respectability politics — the belief that black people can gain white acceptance through respectable behavior — began taking hold in black communities. Many middle-class black Christians eschewed the religious expressions and denominations they’d grown up with, believing them to be too déclassé.

“There used to be an idea — and I don’t think it’s still true — that some blacks, in an effort to gain respectability, kept climbing what they thought was the ladder to the whitest church, which would have been the Roman Catholic Church,” Hayes said. “In other words, if you were a Baptist, you became a Methodist, you became an Episcopalian, you became a Catholic.”

Whether or not the Catholic Church was the whitest church in the country, it is certainly true that a European assimilation model carried the day within most 20th-century Catholic institutions. Even predominantly black parishes were led by white priests and prioritized European-born spiritualities that frowned upon parishioners dancing in the aisles or punctuating homilies with shouts of “Amen!”

This was the state of affairs in the U.S. Catholic Church in 1953, when 15-year-old Bowman traveled the nearly 900 miles from Canton to La Crosse, Wisconsin, to become the first black Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration, the community of sisters that had educated her.

Although Bowman had converted to Catholicism six years earlier, up until that point, she’d always been surrounded by robustly black religious expression. She herself had dabbled in historically black Protestant denominations like the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the Baptist Church before becoming Catholic. But there were no other black Christians in La Crosse, and, according to the authors of the 2009 Bowman biography, Thea’s Song: The Life of Thea Bowman, the void of black spirituality was a shock to the young Bowman.

“It was … a challenge to refrain from whole-body, whole-spirit, whole-voice living,” they write. “She learned it was not ‘proper’ to sashay, to sway, to prance, to dance, to break into song at the least provocation any time of day or night. She strove to please, and mostly she hid her cultural identity.”

“I got a robe up in-a that kingdom. Ain’t-a that good news!”

Two things happened in the 1960s that would electrify black spirituality in the Catholic Church.

First, a swelling black-pride movement convinced many young black Catholics that being black was nothing to be ashamed of. Second, the Second Vatican Council document Gaudium et Spes confirmed what some black Catholics had come to suspect: Black spirituality was just as valid an expression of Catholicism as the European-born spiritualities they’d been taught — that, in fact, they ought to reclaim black spirituality for themselves.

As M. Shawn Copeland notes in the introduction to Uncommon Faithfulness: The Black Catholic Experience, as black Catholics in the ’60s sought more authentic expressions of their faith, there was a proliferation of black Catholic organizations, including the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus and the National Black Sisters’ Conference.

Sister of St. Mary of Namur Roberta Fulton, current president of the National Black Sisters’ Conference, said organizing in such a way was an important step in standing up for the dignity of black Catholics.

“We came together to promote not only positive self-image among ourselves and our people, but to build up the spirituality,” she said. “It was being able to say, ‘Yes, African-American women can be vowed women religious and share our spirituality with the Catholic Church — and bring forth our gift of blackness where we are not just promoting ourselves, but we are always, always wanting to be about the business of our people.’ “

Bowman was one of the founding members of the National Black Sisters’ Conference in 1968 and remained an active member until her death from bone cancer in 1990. In 1980, Bowman became a charter faculty member of the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University in New Orleans, where she taught liturgical worship and preaching.

Just before Bowman died, a group of students from the Institute for Black Catholic Studies visited her at her Canton home. White was among those students, and she recalls that although Bowman had, by that point, largely lost the ability to vocalize, at the end of the visit, she expressed a desire to sing one of her beloved gospel songs.

“For me, that was a testament to the power of black spirituality as a source of healing,” White said. “To heal not only wounds, but to help one cope through times of trouble and immense pain.”

In an interview with Extension magazine given in 1988, several years after she was first diagnosed with cancer, Bowman explained that black spirituality had “long tradition of joy in the face of death.” The old church ladies, in particular, knew that death was nothing to fear because it meant going home to Jesus and to their loved ones.

They’d say, “Soon we’ll be done with the troubles of this world,” Bowman said. “I’m going home to live with my God; I’m going to see my mother.”

[Dawn Araujo-Hawkins is a Global Sisters Report staff writer. Her email address is daraujo@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @dawn_cherie.]

Source: Global Sisters Reporter…